A Very Rude Awakening

by Peter Grose

Allen & Unwin, 2007, 320 pages

Three Japanese midget submarines, each carrying two torpedoes, made an attack

in Sydney Harbor during the night of May 31 and June 1, 1942. Only one midget

successfully launched its two torpedoes with one sinking the depot ship HMAS

Kuttabul and killing 21 sailors. All six Japanese crewmen in the three

midget submarines lost their lives in the attack. A Very Rude Awakening

covers in great depth this unexpected attack that caused chaos among the

warships in Sydney Harbor. The book shows how unprepared Sydney was for the

attack and how responses by senior naval officers were delayed and inappropriate

but later covered up in a report on the incident. Only by luck did Sydney not

suffer more casualties during this night of mayhem. This excellent history,

put together based on valuable contributions by several eyewitnesses and

historical researchers, provides an exciting account of the Sydney attack with

vivid portrayals of the principal persons on the Allied side who were involved

in the battle.

The book's three parts, each with about equal length, thoroughly cover the

preparation, attack, and aftermath of the attack by the midget submarines that entered Sydney

Harbor. Several detailed maps clearly show the most likely paths of the three midget submarines and the two

Japanese reconnaissance flights that took place two and eight days before the attack. Another map lays out the position of the 30 principal

warships in Sydney Harbor at the time when the first midget submarine crossed

into the harbor. The middle of the book contains 12 pages of

WWII and postwar photos. The history focuses on battle participants on the

Allied side but also provides background information, some more detailed than others, for

the Japanese midget submarine crewmen, reconnaissance plane crewmen, and mother

submarine captains. The author convincingly comes to sound conclusions based on

evidence presented, although at times his justified criticisms of action or

inaction by battle participants can come across rather sharply.

A Very Rude Awakening is the first book written by Peter Grose, but

his engaging writing style, in-depth research, and logical presentation of

evidence and conclusions surpass that found in history books written by most

experienced authors. He started as a journalist and then later worked as a

literary agent and book publisher, and his involvement with writing throughout

his career is reflected in this first-class history of the Japanese midget

submarine attack at Sydney Harbor. Grose's second book, An Awkward Truth,

was published in 2009 and covers the February 1942 aerial bombardment of Darwin

by the Japanese. The Acknowledgements section in A Very Rude Awakening

praises the research and generosity of Steven L. Carruthers, who covered the

Sydney midget submarine attack in two books: Australia Under Siege: Japanese

Submarine Raiders 1942 (1982) and an expanded and revised version entitled

Japanese Submarine Raiders 1942: A Maritime Mystery (2006). Carruthers

provided Grose with full access to many valuable interview tapes and files that

he had accumulated over 25 years in researching the attack. The Acknowledgements

section also appropriately gives credit to the many people who kindly assisted

Grose in his research and to key books and written documents that guided him. A

fine history such as A Very Rude Awakening, which covers a complicated

event with conflicting accounts, is the result of not just one author but many

other people over several decades who provided valuable contributions to reach

conclusions on what most likely actually happened.

Several passages explain that midget submarine attacks were definitely not

suicide missions. The two crewmen of each midget sub had food and water to last for a week, and

they were given orders to do their best to return to the mother submarine that

launched the midget. Despite this, midget submarine crewmen recognized that they

had almost a zero chance of surviving a mission. The crewmen were members of the

Special Attack Corps in the same way as kamikaze pilots who made suicide attacks

later in the war, and the Japanese Navy gave them special promotions of two

ranks if they died during the mission. Of the ten midget submarines involved in

the first three attacks at Pearl Harbor, Diego Suarez in Madagascar, and Sydney,

all 20 crewmen except one died, and the one who survived (Kazuo Sakamaki) became

the US's first Japanese POW when he lost consciousness as he washed up on the

beach at Oahu Island.

Part I on "Preparation" discusses six warning signs that could have alerted

Sydney to step up its defenses to prevent or detect sooner the Japanese midget

submarine attack during the night of May 31 and June 1, 1942, but the city's military leaders

made no changes in advance of the attack in order to put Sydney Harbor at an

increased state of readiness. The six warnings that could have signaled an

impending attack are the following:

- May 16 – Japanese submarine I-29 attacked the Russian merchant ship

Wellen with two torpedoes and its deck gun near Newcastle off the New

South Wales coast. Rear Admiral Muirhead-Gould, Naval Officer in Command at

Sydney, closed the harbors at Newcastle and Sydney for one day but reopened

them after a search for the submarine off the coast was unsuccessful.

- May 23 – Nobuo Fujita piloted a two-man Type 0 Small Reconnaissance

Seaplane (Allied nickname of Glen) from submarine I-29 on a spy mission over

Sydney Harbor in broad daylight. At least two eyewitnesses saw the plane,

and a mobile radar station tracked this flight with no thought that it might

be an enemy aircraft. The Combined Defense Headquarters incorrectly

concluded that the radar unit must have something wrong with it, since there

were no Allied planes in the air at that time.

- May 26-31 – On May 26, New Zealand intelligence intercepted a

telegraphic message from submarine I-21, which indicated one or more enemy

submarines were poised off Sydney. On May 30, the message was decrypted. On

May 31, the intelligence digest was distributed to US Vice Admiral Leary,

based in Melbourne as Commander of the Allied Naval Forces in the South-West

Pacific Area, but the information seems to have been either discounted or

ignored, since no notification was sent to those responsible for defending

Sydney.

- May 29 – Japanese submarine I-21 launched a Glen reconnaissance plane

for a spy flight over Sydney Harbor. Pilot Susumu Ito crossed over into

Sydney a little after 4 a.m. The men at Georges Heights Battery saw the

plane and notified the officer on duty, who verified that it was an

unidentified aircraft and reported this to headquarters, but the two

fighters eventually sent to investigate were too late to spot Ito before he

left Sydney. The Glen got caught in spotlights three times, but each time

it went back into the low clouds without being recognized. The Officer of the

Deck on the heavy cruiser USS Chicago (CA-29) recognized the aircraft

as a Japanese Glen reconnaissance floatplane when it flew by the warship,

but somehow this information never got passed on to Rear Admiral

Muirhead-Gould or others responsible for Sydney's defense.

- May 29 – New Zealanders picked up another telegraphic message from a

single submarine (I-21) 40 nautical miles east-south-east of Sydney, but

there is no evidence that this message was ever decrypted. The receipt of an

message from a submarine was communicated to Sydney, but there

was no attempt to increase the city's defenses.

- May 30 – Two midget submarines attacked Diego Suarez harbor in

Madagascar, which damaged an old battleship and sank a motor tanker. The

British did not immediately tell their allies, probably since they did not

want the Japanese to know of the success of the raid and since in the

beginning they were uncertain whether the attackers were Japanese or Vichy

French. As a result, Sydney did not receive any message that they possibly

could be the next place for a Japanese midget submarine attack.

The three Japanese midget submarines that entered Sydney Harbor were

commanded by Lieutenant Keiu Matsuo, Lieutenant Junior Grade Katsuhisa Ban, and

Lieutenant Junior Grade Kenshi Chuman. Chuman's midget submarine, launched from

submarine I-27, crossed Inner Loop 12 into the harbor at 8:01 p.m., but his

midget got caught in the boom net across the harbor entrance. When the two

crewmen realized that they had been detected and had no chance of escape, they

fired the scuttling charges at 10:37, which killed them both. Ban's submarine

from submarine I-24 passed over Inner Loop 12 into the harbor at 9:48 and successfully got around

the boom net that had ensnared Ban's midget. At 10:50, the submarine was fired

on by the heavy cruiser USS Chicago. Ban's craft submerged but was fired

on again at 11:10 when it resurfaced. At 12:29 a.m., the midget submarine fired

two torpedoes at Chicago, but both missed. One of the torpedoes continued

on and sank HMAS Kuttabul with 21 sailors aboard being killed. At 2:04

a.m., Ban's submarine crossed Inner Loop 11 and exited Sydney Harbor. The

submarine never made it back to the mother submarine, and in November 2006 it

was discovered sunk about three kilometers off Newport Reef on the northern

Sydney beaches. Matsuo's midget submarine from submarine I-22 was detected entering the harbor at

10:54 p.m. and was rammed by the anti-submarine vessel Yandra and then at

11:07 was attacked with six depth charges from the same ship. Probably after

waiting patiently near the sea bottom for several hours, Matsuo's submarine finally

crossed Inner Loop 12 into the harbor at 3:01 a.m. He tried to fire his

torpedoes after entering the harbor, but they failed to leave their tubes due to

damage caused by the earlier attack. At 5:15, HMAS Sea Mist attacked and

sank the midget submarine with depth charges. The two crewmen were found later

with shots to the head as they had committed suicide to avoid capture by the

enemy. Both Chuman's and Matsuo's midget submarines were recovered in the days

after the attack.

Rear Admiral Muirhead-Gould, Naval Officer in Command at Sydney, had

responsibility for the unpreparedness for Sydney Harbor's defenses on the night

of the Japanese midget submarine attacks, but the Australian government refused

to set up an independent commission, either public or private, to inquire

officially into what happened but rather allowed Muirhead-Gould to prepare a

report, never intended for the public, about the night's events. Grose explains

the irony of such an assignment (p. 236):

If heads were to roll, then the most likely first head on the block would

be that of the person in charge of Sydney's harbour defences. To put the

entire inquiry into the hands of the man most likely to be its first victim

was about as sensible as asking the average working criminal to conduct his

own trial single-handed, and decide his own sentence. Muirhead-Gould must

have accepted the challenge with relish.

The Rear Admiral's report, with its initial version dated June 22, 1942, and

its final edited version dated July 16 that omits much of the initial criticism

of junior officers, tends to say that defenses worked well even though they did

not. The report's chronology and other explanations contain several factual

errors, some which may have been intentional to hide the faults of top officers

involved and some which have been identified only based on subsequent postwar

research including interviews of participants in the battle and

an examination of documents available from the Japanese side. He incorrectly

concluded that four midget submarines participated in the attack, and he gave a

false time of 10:20 p.m. as to when the Captain of the American heavy cruiser

Chicago left Muirhead-Gould's dinner get-together at his shoreside home,

since he did not actually return to his ship in his launch until about 11:30

p.m. despite his ship being anchored only a couple of minutes away across the

water from the Vice Admiral's home. Grose concludes that Muirhead-Gould's report

entitled "Midget Submarine Attack on Sydney Harbour, May 31st – June 1st, 1942"

met its two real objectives of providing the Navy and Australian government a

defensible narrative as to what happened during the confusing night and

demonstrating that Sydney Harbor's defenses had been up to the mark, which

allowed Muirhead-Gould to get off the hook.

Captain Howard Bode of the heavy cruiser USS Chicago gets presented as

an incompetent and tyrannical leader. He had not yet returned from Rear Admiral

Muirhead-Gould's party at 10:52 p.m., when men aboard Chicago sighted a

midget submarine and fired upon it. When Bode finally returned to his ship about

11:30 p.m., he flew into a towering rage against his officers, called them

"insubordinate jittery fools," and emphatically stated that there were no

periscopes and no submarines. After midnight he accused all of the ship's

officers of being drunk. At 12:29 a.m., the midget submarine piloted by

Lieutenant Junior Grade Katsuhisa Ban fired its two torpedoes within 30 seconds

of each other. They passed by on either side of USS Chicago, and the

second one hit and sank the converted ferry ship Kuttabul, killing 19 Australian

and 2 British sailors. At 2:14 a.m., Chicago left her mooring to proceed

to sea, but Bode still had doubts of the officers' story of sighting and firing

at a midget sub (p. 157):

On the bridge of the Chicago Captain Bode was still not convinced

by his officers' account of sighting and firing at a midget submarine. As

the cruiser steamed up to the harbour entrance Bode turned to Jimmy

Mecklenberg and said: 'You wouldn't know what a submarine looks like.' In

life it is seldom given to anyone to have a perfect riposte to this kind of

remark, but this was Jimmy Mecklenberg's lucky night. 'They looked like

that, Captain,' said Mecklenberg, pointing to a midget submarine passing

down Chicago's starboard side, too close for the guns to depress and

fire at it. The midget was so close that it probably collided with

Chicago, though nobody aboard Chicago felt any impact.

The dictatorial and unreasonable Captain Bode soon met a tragic end. The Navy

conducted a private investigation of Bode's actions during the Battle of Savo

Island in August 1942. When he learned in April 1943 that he had been singled

out for censure due to his questionable decisions during the battle that led to

numerous Allied deaths, he shot himself.

In contrast to the questionable actions and attitudes of the leaders Rear

Admiral Muirhead-Gould and Captain Howard Bode, little known heroes on the

Allied side of the Sydney Harbor midget submarine attack stand out for their

vigilance, prompt action, and determination. Lieutenant Reg Andrew in command of

HMAS Sea Mist took decisive action to destroy Keiu Matsuo's submarine

with depth charges, although he did not get the credit he deserved as he was

intentionally sidelined by superiors for most of the war. Lieutenant Commander

Jimmy Mecklenberg assumed command of Chicago when Captain Bode had not

returned from his dinner party at Vice Admiral Muirhead-Gould's house.

Mecklenberg

issued prudent commands to get Chicago prepared to go to sea and to have

the destroyer escort Perkins conduct screening patrols around Chicago.

Nightwatchman Jimmy Cargill rowed over and investigated Chuman's midget

submarine caught in the boom net. He made efforts to report his findings, but

some men in positions of responsibility were skeptical of his story that there

could be a midget submarine in the net. Roy Cooté and Lance Bullard were the

principal divers to recover bodies from the sunken depot ship Kuttabul

and to investigate and recover the two midget submarines that had been sunk in

the harbor. They demonstrated sustained courage in diving for more than a week

and especially when they first approached Matsuo's submarine, which was still

considered to be alive at the time with the possibility of explosive charges

aboard being detonated while they were near.

The Japanese side of the midget submarine attack on Sydney Harbor receives

less attention than the Allied side, but Grose provides enough details and

background to get a basic understanding of their strategy and thinking.

Lieutenant Keiu Matsuo, one of the principal strategists of Japan's midget

submarine program, has his personal history presented, whereas the book includes

few details about the other midget submarine crewmen since less is known about

them. The book also provides background information about the midget submarine

attacks at Pearl Harbor and Diego Suarez in Madagascar. Details of

reconnaissance flights carried out by Susumu Ito and Nobuo Fujita offer

fascinating insights into the dangers that they each faced as a pilot of a Glen

reconnaissance floatplane launched from an I-class submarine.

The thoroughness, objectivity, and writing style found in A Very Rude

Awakening make this history the best of several books about the Japanese

midget submarine attack on Sydney Harbor. The author Peter Grose readily

acknowledges his debt to researchers and writers who went before him. His

analysis at times leads to different conclusions than those widely accepted in

the past, but his reasoning and inferences based on available evidence seem

sound.

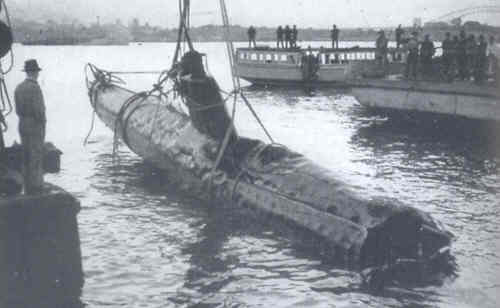

"Postcard produced by the Royal Australian Navy and sold as a

souvenir of the submarine attack. This particular postcard shows the

fearful beating from depth charges suffered by Matsuo's midget.

The massive dent behind the conning tower is clearly the result of a

depth charge detonated at very close range. It may well be the

outcome

of Reg Andrew's first attack in Taylors Bay."

(6th page of photos between pages 148 and 149) |