|

|

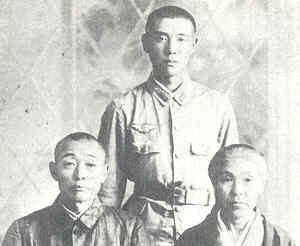

Saburō Miyagawa with parents.

Photo taken during return home

when in training at Sendai

Pilot Training School.

|

|

|

|

Miyagawa was assigned to the 104th Shinbu Special Attack

Squadron to sortie on a special attack mission from Bansei Air Base. The squadron

divided into two groups of six planes each that made sorties on April 12 and 13,

1945, but Miyagawa had to return to base due to engine problems. He said he

wanted to make a sortie again quickly in a good plane, but he was sent to nearby

Chiran Air Base to wait for orders. During his wait, he by chance met a former

Ojiya Elementary School classmate named Yoshikatsu Matsuzaki. However,

Matsuzaki made a sortie on a special attack mission on May 20. Miyagawa finally received

his order to make a sortie from Chiran. June 5, the day before his scheduled sortie to

death, was his 20th birthday. He visited Tome Torihama and her two daughters at

Tomiya Restaurant, where he told them that he and his friend Enosuke Takimoto

would both return as fireflies at 9 o'clock the following night. They took off

together the next day, but Takimoto signaled many times to Miyagawa that they

should return to base due to driving rain and heavy clouds. Miyagawa signaled

that Takimoto should return and he would go on. On the evening of June 6,

Takimoto returned alone to Tomiya Restaurant. At 9 o'clock, a firefly came

through the open restaurant door and alit on a ceiling beam. Everyone in the

restaurant marveled that Miyagawa had returned as a firefly.

Much of this book strays far from the life story of Saburō Miyagawa. Chapter 2's fifty pages, organized by season starting with spring, at

times reads like a tour guide for the region in Niigata Prefecture where

Miyagawa lived and went to school. The author describes the region's festivals,

wildlife, foods, farming activities, sports, and plants, but Miyagawa's name

only gets mentioned now and then as part of these general depictions of the

region. As another example of the book's digressions, the end of Chapter 1

tells the stories of ten other Special Attack Corps pilots who made sorties from Chiran, but

these pilots had almost no direct connection with Miyagawa. As a final example,

Chapter 6 goes into much more detail about Tome Torihama's life than needed for

a book intended to be Miyagawa's biography.

Besides many extraneous details contained in this book, the

idealization of Miyagawa's life makes this biography rather tedious. Although

he may very well have been outstanding in many respects, Miyagawa seems based

on this book to never have done anything wrong, excelled in academics and

sports, and treated everyone kindly. Not only that, he was an idol for all the

local teen girls. Hiroi gathered much information for this book from secondary

sources, but he also interviewed some family members and friends, who may have

been hesitant to say anything negative about someone they consider to be a hero

who died defending his country.

Although the bibliography includes several standard books on

Chiran and the Special Attack Corps pilots who made sorties from there, the author still commits

a few errors. For example, he states that 1,028 Special Attack Corps pilots died in sorties

from Chiran Air Base. Actually, this number includes all Army airmen who died

in attacks around Okinawa. Only 439 of these men made sorties from Chiran. In

another lapse, the author states Miyagawa would encounter the American fleet

within an hour after leaving the mainland, but his actual flying time would

have been about two hours.

The book contains several touching stories, but these tend

to be brief with few specifics. Enosuke Takimoto, who had made a sortie with Miyagawa

but returned to base due to poor weather, traveled right after the war's end from his home

in Yamanashi Prefecture to Miyagawa's parents' home in Niigata Prefecture.

Takimoto stayed at their home for a month as they treated him just like their

son, but they never met again as he passed away just three years later. In another

moving story, on the eve before Miyagawa's special attack sortie, Tome Torihama's

14-year-old daughter Reiko received from Miyagawa his flight watch and his

treasured fountain pen given to him by his brother Eijirō when they worked

together at Tachikawa Aircraft Factory. Miako, Reiko's older sister, said

years later that if Miyagawa had lived he might have married Reiko when she

grew up. The book also tells of the emotional meetings of Tome Torihama with Saburō's brother Buichi in 1970 at a Tōkyō television studio and his brother

Eijirō in 1982 at Chiran.

This biography of Saburō Miyagawa contains much information

that other books do not mention about his short life. However, this book

suffers from excessive and irrelevant details in many places. A much shorter

book, maybe about one third of its current size, would have given the key episodes of

Miyagawa's life much more emotional impact.

|