|

|

|

|

First Lt. Hajime Fujii [1]

|

|

|

Censored Suicide

Written by Bill Gordon for May 2006 reunion of U.S.S. Drexler Survivors Reunion Association

Japan's Ministry of Home Affairs squashed publication of the

tragic story of First Lieutenant Hajime Fujii, an instructor at Kumagaya

Army Aviation School. In December

1944, Fujii's wife Fukuko committed suicide along with their two children, Kazuko

(age 3) and Chieko (age 1), so that her husband could freely go on a special attack

(suicide) mission. Due to government censorship, the story remained unknown to the Japanese public for

many years after war's end.

This article draws information from several Japanese books to put

together the history of Hajime Fujii and his family [2]. The sources contain some conflicting details, which

are explained in the article's Notes section. The

primary sources are Sange no kokoro to chinkon no makoto (Spirits of

heroic dead and devotion to repose of souls) (1995, 123-5) edited by Yasukuni

Jinja and Tokkō no machi: Chiran (Special attack corps town: Chiran)

(2003, 171-84) by Sanae Satō.

Hajime Fujii, born on August 30, 1915, grew up in Ibaraki

Prefecture as the eldest son of a farming family with seven children [3]. His

parents wanted him to take over the family farm, but he volunteered for the

Army. He joined as an infantryman in a

machine gun squadron and displayed exceptional ability. He was sent to the

front in China, where Japan had been at war since 1931. While in China, a mortar shell wounded

him in the left hand. During his recovery there, he first met Fukuko.

Fukuko grew up in a merchant's family in Takasaki City

in Gunma Prefecture. The family had three girls, and she enjoyed playing the

piano and singing. She was working as a field nurse in China when she met

Fujii, and they soon decided to get married. They had a love marriage rather

than an arranged marriage typical at that time in Japan.

Due to Fujii's exceptional skills, he was selected to enter

the Army Air Corps Academy. Sources do not indicate

his area of specialization, but one source states he did not volunteer as a

pilot since he could not tightly grip a plane's control stick due to the mortar

shell wound to his left hand suffered in China [5]. After graduation in the

spring of 1943, he went to Kumagaya Army Aviation School as a company commander

in charge of students' character building and mental instruction. He told his

students, "If needed, crash your aircraft into an enemy camp or into an enemy

ship." As Fujii explained to his students the concepts of loyalty and

patriotism, he repeatedly said, "I will not let only you die. I as your

company commander also will surely go."

|

|

Fukuko with oldest

daughter Kazuko [4]

|

|

|

|

Fujii, with a motto that "words and deeds should be

consistent," was strict with himself and volunteered for the special

attack force (tokkōtai in Japanese). Perhaps as an educator he had a guilty conscience since he had

his students go on kamikaze attacks but he stayed safely behind. He

volunteered even though it was not expected for someone in his position to be

selected for the special attack force since he had a wife and two young

children. Army leaders rejected Fujii's two written petitions [6]

to

join the special attack force, probably because he held an important post as

commander at Kumagaya Aviation School and he had a family.

Fukuko initially opposed her husband's joining the special

attack force, but in time she came to

understand her husband's firm determination to join his students to attack the

enemy. On December 14, 1944, she left the house with her two young daughters,

went to Arakawa River near Kumagaya Aviation School, and

jumped into the frigid water with her daughters.

The next morning on December 15, the three dead bodies were

discovered. The two young girls wore their finest kimonos, with one-year-old

Chieko carried on her 24-year-old mother's back and three-year-old [7]

Kazuko's

hand tied with a rope to her mother's hand.

Fujii was contacted at Kumagaya Aviation School [8]. He hurried

to the spot in a police car with Warrant Officer Shimada, who could find no

words of consolation since the tragedy was so great. Fujii said with a moaning

voice, "Perhaps today I will shed tears. Please forgive me for only today.

Please understand." In order to hide his tears, he crouched down before

the three lifeless bodies and gently brushed sand off their white skin. "I

am always telling my students to commit themselves totally to be ready to die,

but I myself cannot devote myself this far."

Fujii later found Fukuko's final letter [9], which included

the following words: "Since you probably would be worried about us and not

be able to freely carry out your duties because we are here, we go ahead before

you and will wait for you. Please fight without reserve."

During the evening after the funeral of Fujii's wife and two

daughters, he wrote the following letter to Kazuko, his oldest daughter:

A cold, blustery December day

Your life disappeared as dew on Arakawa River's bank. It is

painfully sad that together with your mother you sacrificed yourself ahead of

your father because of his fervent desire to lay down his life for his

country. However, I hope that you, who as a young girl vanished together with

your mother, will be gladly smiling.

Father also will soon be able to follow after you. At that

time I'll gladly hold you close to me as you sleep. If Chieko cries, please

take good care of her. Well then, goodbye for a short time.

Daddy will perform a great feat on the battlefield and bring

it as a present for you. Both you and Chieko, please wait for me until then.

He wrote on the cover of the letter, "December 15,

1944, 1 a.m., Kazuko Fujii, item left behind." The time of 1 a.m.

apparently refers to the estimated time of her death. Fujii's younger sister

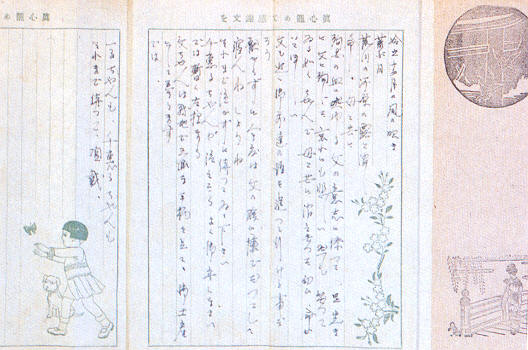

preserved this letter, which is shown below.

Fujii's letter to his daughter Kazuko [10]

Although the Army and government banned any publication of details concerning the deaths of Fujii's wife and her two children, the

officers and students at Kumagaya Aviation School heard rumors and pieced together much of what had happened. After the death of Fujii's wife and

daughters, he wrote a petition in his own blood asking for the third time to

join the special attack force so that his wife's death would not be useless [11].

This time the Army leaders considered the unique circumstances and

appointed him as a special attack force member. When he left Kumagaya Aviation

School, the students and staff officers held a farewell party and gave him a sword purchased with money

from their savings. Fujii was very glad. He pulled out the sword and raised it

high over his head shouting, "With this I'll chop those guys down until

not one of them remains!"

|

|

|

|

First Lieutenant

Hajime Fujii [12]

|

|

|

On February 8, 1945, the 45th Shinbu Squadron was formed to

carry out kamikaze attacks, and Fujii was appointed as its commander. The squadron of twelve men included

nine Ki-45 Type 2 Toryu Fighters (Allied code name of "Nicks"), with three

aircraft manned by both a pilot and a radio operator/gunner. The squadron was named Kaishin, which

means "cheerful spirit" in Japanese.

The squadron trained together at several air bases, including

Hokota Air Base in Ibaraki Prefecture and Matsudo Air Base in Chiba Prefecture.

Fujii wrote the following letter to the mother of a family who cared for him

while at Matsudo Air Base [13]:

May 21, 1945

Dear Aiko Hirano,

I want to thank you very much for the delicious meal you

served the other day. Thank you also for the long trip you took to see me off

when I left.

Please say hello to everyone in your family. The flowers

given to me by your daughters now decorate my room in faraway OOO [14].

Well then, I surely will do my duty with all my heart.

On May 27, 1945, the 45th Shinbu Squadron flew to Chiran Air

Base in Kagoshima Prefecture for the scheduled sortie to Okinawa the next

morning. Before his sortie, Fujii wrote to Fukuko's father, "I look

forward to being able to see Fukuko, Kazuko, and Chieko."

The squadron's nine aircraft, commanded by Fujii as the radio

operator/gunner in the lead aircraft, made a sortie from Chiran at about 5 a.m. on May

28, 1945 [15]. On the

way to Okinawa, one aircraft crashed into the sea, and inhabitants of a small island

rescued the pilot. The squadron's remaining eight aircraft reached Picket Station

15, about 45 miles northwest of Nago Bay on the western side of Okinawa. Two

destroyers, Drexler and Lowry, and American Combat Air Patrol

(CAP) fighters shot down most of the squadron's aircraft. However, two aircraft

crashed into Drexler, causing the destroyer to sink in less than a

minute after the second plane hit. Nearby landing craft support vessels rescued

199 survivors, but 158 of Drexler's officers and crew died in the attack

by Fujii's squadron.

The family grave of Fujii, Fukuko, and their two daughters

stands on top of a small hill in Mitsukaidō City, Fujii's hometown in

Ibaraki Prefecture. Each year a group of Fujii's former students at Kumagaya

Aviation School visit the family grave to pay their respects. Fujii was very popular

with the students. His instruction was strict, but since he was kind-hearted,

everyone admired, respected, and trusted him. When former students visit

his grave, each year they sing the song "Shōwa Momotarō (Peach Boy) [16],"

whose lyrics were composed by Fujii in 1944. The first two verses go as follows:

1

Propeller glittering on his chest

Shōwa Momotaro taking off to the sky

An eaglet with splendid wings

Doing barrel rolls, reverse turns, loop-the-loops

Showing talents of Japan's young men

We youth pilots

2

Loyalty and filial piety nurtured

With a feeling of gentle love

Kudan Hill [17] where will bloom

Ah, we will make that mother

The best mother of Japan

Determined youth pilots

Fujii was in the 21st Class of the Army's Second Lieutenant Cadets. He

received a posthumous two-rank promotion to Major after his death in a special

attack. [18]

Notes

1. Source of photo: Asahi Shimbun Seibu Honsha 1990, 45.

2. Principal sources for this article: Asahi Shimbun Seibu Honsha 1990, 43-5;

Kōsaka 2003, 17-25; Osuo 2005, 139-42; Satō 2003, 171-84; Yasukuni Jinja 1995,

123-5.

3. Asahi Shimbun Seibu Honsha (1990, 44) states that Fujii grew up in a family with

six children. Satō (2003, 171) indicates seven children in his parents' family.

4. Source of photo and

caption: Yasukuni Jinja 1995, 124.

5. Satō 1997, 171.

6. Asahi Shimbun Seibu Honsha (1990, 43) and

Kōsaka (2003, 19) state that Fujii submitted two or three written petitions for the special attack force

that the Army rejected. Satō (2003, 179) states that the Army rejected two of

Fujii's written petitions.

7. Kōsaka (2003, 19) indicates that Kazuko was

four years old when she died. Asahi Shimbun Seibu Honsha (1990, 43) and Yasukuni Jinja

(1995, 123) state she was three years old.

8. Kōsaka (2003, 19-20) states that Fujii came

home on December 14, 1944, as he normally did and found Fukuko's last letter to him on

top of the desk. He was then notified at home by police the next morning that the bodies

of his wife and two daughters had been found.

Satō (2003, 174-5) states that Fujii was away for one week, staying at Kumagaya Aviation

School, when his wife committed suicide. The police notified him at the school,

and he went by police car to the place where the bodies had been found.

9. Kōsaka (2003, 19-20) states that Fujii

found Fukuko's last letter before he was notified by police that her body had

been located. Satō (2003, 175-6) implies that he found Fukuko's last letter

after he went with police to view the dead bodies.

10. Source of image: Yasukuni Jinja 1995,

first page of photos in front of book.

11. Kōsaka (2003, 20), Satō (2003, 179-80),

and Yasukuni Jinja (1995, 124) indicate that Fujii's petition in his own blood

was written after Fukuko's suicide. However, Asahi Shimbun Seibu Honsha ( 1990,

43) indicates that his petition and its acceptance by the Army occurred before

Fukuko's death.

12. Source of photo: Yasukuni Jinja 1995, 123.

13. Chiran Kōjo Nadeshiko Kai 1996, 70-1.

14. Army officers censored letters to

ensure no military secrets were revealed. The location where Fujii wrote this

letter was marked out by censors and is indicated by "OOO."

15. The information in this paragraph comes

from my article entitled "Who Sank the Destroyer Drexler?"

(http://www.kamikazeimages.net/stories/drexler/index.htm).

16. Shōwa refers to the period that Emperor

Hirohito reigned in Japan (1926-1989). The word Shōwa means "enlightened

peace." Momotaro, which is often translated as "Peach Boy" in

English, is a legendary Japanese hero who together with his animal friends

defeated ogres living on an island who were ravaging the land and killing the

people.

17. Kudan Hill is location in Tōkyō of Yasukuni

Jinja, Japan's national shrine to honor the spirits of soldiers killed in

battle.

18. Chiran Tokkō Irei Kenshō Kai 2005, 162.

Sources Cited

Asahi Shimbun Seibu Honsha. 1990. Sora no kanata ni

(To distant skies). Fukuoka: Ashishobō.

Chiran Kōjo Nadeshiko Kai (Chiran Girls High School Nadeshiko

Association), ed. 1996. Gunjō: Chiran tokkō kichi yori

(Deep blue: From Chiran special attack air base). Originally

published in 1979. Kagoshima City: Takishobō.

Chiran Tokkō Irei Kenshō Kai (Chiran Special Attack

Memorial Society), ed. 2005. Konpaku no kiroku: Kyū rikugun tokubetsu

kōgekitai chiran kichi (Record of departed spirits: Former Army Special

Attack Corps Chiran Base). Revised edition, originally published in 2004. Chiran Town, Kagoshima

Prefecture: Chiran Tokkō Irei Kenshō Kai.

Kōsaka, Jirō. 2003. Tokkō kaerazaru wakumonotachi e no rekuiemu

(Requiem for young men of special attack corps who did not return). Tōkyō: PHP

Kenkyūsho.

Osuo, Kazuhiko. 2005. Tokubetsu kōgekitai no kiroku (rikugun hen)

(Record of special attack corps (Army)). Tōkyō: Kōjinsha.

Satō, Sanae. 2003. Tokkō no machi: Chiran

(Special attack corps town: Chiran). Tōkyō: Kōjinsha.

Yasukuni Jinja, ed. 1995. Sange no kokoro to chinkon no makoto

(Spirits of heroic dead and devotion to repose of souls). Tōkyō:

Tentensha.

|